Drunk Democrat in Texas Wearing Dress in Gay Band

Abstract

The Spanish Town parade is currently the largest Carnival parade in Baton Rouge, Louisiana with hundreds of thousands of attendees dressed in pink costuming, cross-dressing, and wearing pink flamingo paraphernalia. This chapter traces the queer origins of the Spanish Town parade to the racially integrated bohemian gayborhood of Spanish Town in the 1980s. Using interviews, archival research, and participant observation, I argue that current LGBTQ residents of Baton Rouge, even those who have never lived in Spanish Town, claim a vicarious citizenship to the neighborhood and parade through an understanding of the queer origins of the parade in the 1980s and the parade's beginning in a gayborhood. This vicarious citizenship is tempered by the heterosexualization of the contemporary Spanish Town parade. Although LGBTQ residents still attend the parade in large numbers, there is more ambivalence about the homophobic imagery in the parade and the consumption of gay culture by heterosexual parade participants.

Keywords

- Spanishtown

- Baton Rouge

- Carnival

- Pride parade

1 Introduction

Spanish Town, one of the oldest neighborhoods in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, is a small neighborhood built in 1805 by Canary Islanders who had moved from Spanish-ruled Galvez Town (Isch 2016). The Spanish Town neighborhood is not now nor has it ever been an ethnic urban enclave and it has had a complex history of racial segregation and integration. During the 1980s, the Spanish Town neighborhood developed a reputation as a bohemian neighborhood and gayborhood and began staging a neighborhood Mardi Gras parade. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people were visible in the neighborhood and parade during this time, with the most visible participation being from white gay men. The Spanish Town parade is now the largest Carnival parade in Baton Rouge, with hundreds of thousands of attendees dressing in pink costuming, cross-dressing, and wearing pink flamingo paraphernalia. In the 2010s, the event has retained some of its queer cultural influence, even as it is predominately organized by white heterosexual men.

This chapter traces the queer origins of the Spanish Town parade to the racially integrated bohemian gayborhood of Spanish Town in the 1980s. Although there are competing accounts of how the parade began, many LGBTQ residents of Baton Rouge describe a narrative of the parade as being started by drag queens in a gayborhood. I argue that current LGBTQ residents of Baton Rouge, even those who have never lived in Spanish Town, claim a vicarious citizenship in the neighborhood and parade through an understanding of the queer origins of the parade in the 1980s and the parade's beginning in a gayborhood. Greene (2014) has defined vicarious citizenship as "the exercise of rights and entitlements to community participation emanating from extra-neighborhood, symbolic ties to a neighborhood or locality" (99). This vicarious citizenship is tempered by the heterosexualization of the contemporary Spanish Town parade. Although LGBTQ residents still attend the parade in large numbers, there is more ambivalence about the homophobic imagery in the parade and the consumption of gay culture by heterosexual parade participants.

2 Consuming Gay Culture

The heterosexualization of the parade and neighborhood is related to the larger processes of historic preservation and second-wave gentrification in the neighborhood, along with tourism and the growing popularity of the parade, the largest Mardi Gras parade in Baton Rouge. The heterosexualization of previously gay-focused events and spaces is connected to a long history of heterosexuals consuming gay culture as a spectacle. This consumption focuses on the aspects of gay culture most easily consumed by heterosexual audiences such as aesthetics, camp, and drag (Stone 2016).

Many scholars study the way the culture of marginalized groups is commodified or viewed as a spectacle (Crary 2001; Debord 2012; Wetherell et al. 2001). In Gay New York, historian Chauncey (1994) describes the way neighborhoods like the Bowery and Harlem were a spectacle that white, middle-class observers would derive pleasure from visiting. Visitors can engage in "slumming it," temporarily participating in cultural events sponsored by marginalized groups without said visitors challenging their own ideas about that culture. Some festival attendees may still be "tourists" visiting "gay Disneyland," as part of a long history of heterosexuals consuming the experience of being in gay spaces, particularly gay bar spaces (Heap 2008; Orne 2017). Throughout his work, Boystown, Orne (2017) describes how straight women participating in gay spaces disrupts the sexual energy and culture of these spaces, and gay men often resent the intrusion of these women. In more ambiguous gay spaces like temporary festival spaces, these processes of slumming it or being a tourist may be more obscure. In these temporary spaces "the deliberate consumption of queerness" is complex in places "where queerness is performed and visible but where it is not always evident who is the consumer and who is the consumed, and where the consumer regulates production in ways that are difficult to discern" (Rushbrook 2002: 198).

Conversely, participation in LGBTQ events by heterosexual participants may increase a sense of community for all participants. Sociologists have long observed that when people come together to enjoy something—whether that be a religious ritual, holiday, or festival—it creates a sense of community (Delanty et al. 2011). Browne articulates that "where celebration moves to imagined connections between individuals, there is a sense of collective partying" (Browne 2007: 75). Collective partying may be a "cultural bridging practice" that temporarily brings together diverse individuals for a common purpose (Braunstein et al. 2014). For example, these LGBTQ events with broad heterosexual attendance may also be a temporary reprieve from heteronormativity for participants and a challenges to internal homophobia or transphobia. Heterosexual participants, in studies of drag show and talk show viewers, often interrogate and challenge their own understandings of gender and sexuality (Gamson 1998; Rupp and Taylor 2015).

3 Baton Rouge Mardi Gras and the Spanish Town Parade

A common misconception about Mardi Gras is that the festival is a long weekend of debauchery celebrated in New Orleans in which drunk college students display their breasts to get beads and trinkets during parades. Mardi Gras is celebrated all along the Gulf Coast, from Galveston, Texas, to Pensacola, Florida, in both cities and rural areas. The festival is a season—the Carnival season—that runs from the day of Epiphany in January to Fat Tuesday or the beginning of Lent, which is typically in early March. Compared to the extravagant tourist spectacle and traditions of New Orleans Mardi Gras celebrations, Baton Rouge Mardi Gras parades and balls have always been considerably smaller in size. A network of private organizations called krewes run parades and host private balls that are a central part of the local residents' celebrations of the event. The ritual disrobement (or "boobs for beads") in the French Quarter of New Orleans is the exception rather than the rule for Carnival parades, most of which prohibit such nudity. Most krewe members who ride in parades throw beads, candy, and toys to all attendees—children and adults.

Baton Rouge has a limited history of parading, and none of the parades reach the scale of the popular New Orleans Carnival parades. Few krewes regularly paraded in the city of Baton Rouge until after World War II (Costello 2017). The Spanish Town parade began in 1981 and has since grown into the largest parade in the city. The Society for the Preservation of Lagniappe in Louisiana (SPLL) was founded in the 1980s to organize the parade and, later, the Spanish Town Ball. The parade grew so quickly that in 1985 it was protested against by Jimmy Swaggart and his ministry for questionable material (Hall 2016).

From the beginning, the parade themes emphasized the bohemian and tacky style of the parade. The 1982 parade theme was "Everyman a King", which was both a play on Huey P. Long's slogan for governor in the 1930s and on the ritual inversion of Carnival, in which the peasant becomes "king for the day." The most infamous theme was "Poor Taste is Better Than No Taste At All" in 1986, the same year that the plastic pink flamingo was adopted as the symbol of the parade. This theme became the kitschy placemaking narrative of the neighborhood, as residents embraced the tackiness of pink flamingo decorations on their lawns (Donlon, n.d.). One interviewee in this study who had lived in the neighborhood for several decades stressed that the flamingo became the symbol of the parade because gay Spanish Town residents often put them in their front yards.

The Spanish Town parade is definitely the largest Carnival parade in Baton Rouge history. In the 2010s, newspapers consistently report that over 150,000 attendees each year crowd the streets in and around the Spanish Town neighborhood to watch floats and walking krewes depicting political and social satire. Each float or walking krewe is organized by a "krewe," a term for private organizations that stage Mardi Gras parades and balls (Kinser 1990). These krewes are typically small groups of ten to twenty friends in the Spanish Town parade, with comical names like Krewe of Konfusion, Krewe of Damnifineaux, BeignYAYS, S'Krewe U, and Krewe of Mixed Nutz. Someone in the group has access to a truck and flat-bed trailer, which is lavishly decorated with flashy, tacky decor. Krewes throw traditional Mardi Gras beads and doubloons to the crowd, along with t-shirts, stuffed animals, candy, and items of dubious value, such as slices of day-old bread, CDs, and beer bottle tops. The entire parade is coordinated by SPLL, which is part of a 501(c)3 non-profit corporation that has donated over $500,000 to local charities (Hall 2016).

4 Methods

The data in this chapter comes from multiple sources. First, studying the Spanish Town parades was one component of a five-year four-city comparative study of LGBTQ involvement in urban festivals of the South and Southwest, focusing on LGBTQ belonging and cultural citizenship in these four cities. Mardi Gras in Baton Rouge and Mobile, Alabama, were the two sites in which I studied LGBTQ Carnival history and current events. All data collection—including interviews and participant observation research—was approved by the Trinity University Institutional Review Board. In Baton Rouge, I attended multiple Carnival masque balls, parades, and other events, along with Carnival museum exhibits, archives, and academic presentations. Elsewhere I have written about the Krewe of Apollo of Baton Rouge, a Mardi Gras krewe run by gay men who put on an annual Carnival ball that over one thousand people attend (Stone, forthcoming).

Most of the research for this chapter comes from my data collection at the Spanish Town events, where I examined both contemporary practices of the parade and asked participants questions about the history of the parade and the Spanish Town neighborhood. I attended the Spanish Town parade twice (2014 and 2016). At each parade I arrived early and walked along the hundreds of floats as they were being queued up before the parade. I took thousands of pictures of the content on the floats, chatted with float riders, collected ephemera, and took tours of a few floats. During the parade, I experienced the procession from multiple vantage points, including the exclusive judges' platform and the informal "gay area" and "family area" of the parade. I talked extensively with dozens of parade attendees about why they were at the parade, how often they came, and what they enjoyed. I met up with members of the Krewe of Apollo and attended house parties in the homes of gay men who lived in the neighborhood. These activities allowed me to understand the nuances and complexity of a large event like the Spanish Town parade. I also attended the Spanish Town Ball (2015), and a meeting with Spanish Town organizers while they painted the flamingo cut-outs for the annual "flocking" (the placement of pink wooden flamingos in a Baton Rouge lake).

This participant observation work was triangulated with interviews and archival research that I conducted in the summer, outside of Carnival season. These interviews provided important history and context for Spanish Town events. As part of my broader study on Baton Rouge Mardi Gras, I formally interviewed 21 Baton Rouge residents involved in local Mardi Gras events, three of whom were involved as organizers of early Spanish Town events. Almost all LGBTQ interviewees attended or participated in Spanish Town events in some way. We informally interviewed dozens of Spanish Town Parade and Ball participants. My research assistant and I spent an evening having dinner with one Spanish Town krewe of lesbian, bisexual, and queer (LBQ) women, and we informally interviewed members of several other krewes during Spanish Town events. I also incidentally interviewed a group of white gay men in Mobile, Alabama, who annually drive to Baton Rouge to be part of a Spanish Town parade krewe. These interviews, which provided insight into the perceptions and experiences of the Spanish Town parade, were supplemented with historical research on the origins of the parade.

We collected archival information on Spanish Town from the Baton Rouge Public Library Archives and the Louisiana State University archives. The LSU archives included surveys of the Spanish Town neighborhood in the 1980s by architecture student Thomas Chandler.

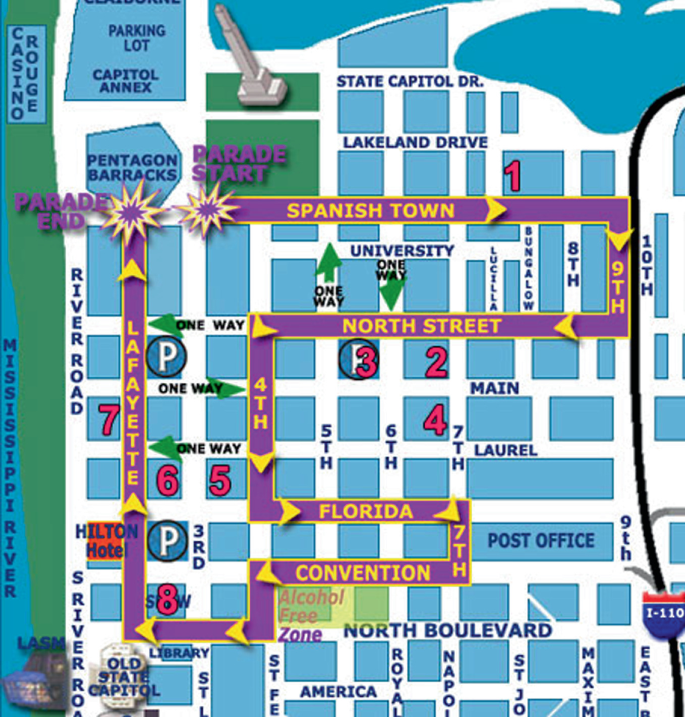

Below, I use Chandler's study to illustrate the development of the Spanish Town neighborhood as a bohemian gayborhood in the 1980s and the origins of the Spanish Town Parade during this time (see Fig. 6.1). Then, I compare the origins of the parade with ethnographic impressions during the 2010s.

Map of Spanish Town parade

5 The Bohemian 1980s in Spanish Town

The Spanish Town neighborhood has a complex history of racial segregation and integration as it developed into a bohemian gayborhood. After Spanish Town was razed by Union forces in the Civil War, formerly enslaved Black residents lived in the neighborhood until it was gentrified in the 1930s by white students and staff of the newly built Louisiana State University (LSU) campus nearby. Catholic families moved into the neighborhood in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1957, the federal government constructed an interstate highway that ran through Baton Rouge and bisected the Spanish Town neighborhood. The plummeting oil market and white flight related to school desegregation emptied out Spanish Town in the 1970s (Hall 2016). It was in the 1970s and 1980s that Spanish Town developed a bohemian reputation, a "healthy wild streak" as gay men flocked to the neighborhood (Hall 2016). One white senior citizen man who we interviewed described the residents of the neighborhood in the 1970s and 1980s as, in his words, "fruits without money" (in contrast to what he described as the "fruits with money" who live in the neighborhood now).

The work of Chandler (1985) set the groundwork for understanding the 1980s in the Spanish Town neighborhood. Completed in 1985, his study surveyed residents of the Spanish Town neighborhood about their sense of neighborhood as place, along with interviewing select residents in depth about their homes and neighborhoods. All of the surveys were archived at Louisiana State University, and the interviews were described in detail in his master's thesis. The surveys and interviews provide insight into how residents of Spanish Town in the early 1980s understood their neighborhood, along with signs of how the neighborhood had changed into a bohemian gayborhood. Below, I use responses to this survey to capture the feel of the Spanish Town neighborhood in the 1980s.

Many residents described the neighborhood as eclectic and diverse in their surveys. White married couple Paula and George described their first Mardi Gras in Spanish Town. This couple described the bohemian feel of the Baton Rouge, Louisiana, neighborhood of Spanish Town in the early 1980s, including groups affiliated with the Spanish Town Parade (the Merry Minstrels and The Sluts of '84 who dressed in drag). After moving to the neighborhood a month earlier, they invited a few neighbors over for the parade and their small gathering turned into a large house party:

By the end of the day, we had everybody; I mean we had heterosexuals, homosexuals, drag queens, blacks, whites, people we had never seen before, The Merry Minstrels, The Sluts of '84, people in ape suits, Superman, dope smokers out on the back balcony…We had a really wonderful time, and even though we didn't know any of these people—and some of them looked pretty shady—everyone was so well behaved. There was not a mar or a scratch anywhere. We had a great time. (Chandler 1985: 47–48)

Costuming is common during parades, so people in ape suits, drag, and dressed as Superman mingled with each other. Like many other residents, Paula emphasized the ways that everyone got along despite their diversity.

One of the most common themes in these surveys was describing the Spanish Town neighborhood as tolerant in a distinctly bohemian or counter-cultural way. One young white woman who lived in Spanish Town with her young husband and baby described Spanish Town as "a neighborhood. It is not a subdivision with people buying starter homes or whatever. People speak to each other on the street and tourists get lost here regularly" (Chandler 1985: 67). One interviewee of Chandler's project described that the counterculture had been much stronger in the Spanish Town neighborhood in the 1970s and had kind of quieted down since then, but another Spanish Town resident wrote on their survey that the neighborhood "possesses more people (than other areas) who still live in a counter-culture type reality—therefore there's much more tolerance, like color" (Chandler 1985: 84). One young single white woman wrote that "Spanish Town is unique! Just on my block, the consistency is: Black, senior citizens, young couples, young singles, students and people like me, not to forget the gays. The amazing thing is that everyone lives and accepts each other" (Chandler 1985: 139). These descriptions of the counterculture in Spanish Town parallel understandings of bohemian laxity and openness to diversity in other American neighborhoods like Greenwich Village, which had a reputation for tolerating non-conformity, eccentricity, and "artistic types" (Chauncey 1994: 229).

Like Greenwich Village, the tolerance for racial diversity was relative to a history of racial segregation in Baton Rouge and the neighborhood itself and may have been limited. Baton Rouge was the site of the first successful bus boycotts in the 1950s, the model for future civil rights boycotts in Montgomery and Tallahassee (Sinclair 1998), but it is currently one of the most racially segregated cities in the South (Yee 2015). The neighborhood had gone through a history of being a predominately Spanish Canary Islander neighborhood, a battleground for the Civil War, a predominately Black neighborhood, a gentrified white professional and Catholic family neighborhood, an abandoned neighborhood, and then a racially integrated bohemian neighborhood. Black residents of Spanish Town in the 1980s may have been aware that they were living in a neighborhood that at one time had been a predominately Black neighborhood. One Black resident of Spanish Town recalled that before the building of LSU in 1936 a local road used to be called "Slocum Alley" before it was called University Walk and that Black doctors and professors lived in the neighborhood. The racial integration of Spanish Town neighborhood was a conflictual process, as many survey respondents described white flight out of the neighborhood. One single white elderly woman who had lived in the neighborhood for 64 years wrote that "When they started renting to the Negros, some white folks moved out" (Chandler 1985: 103). When the interstate was built through Spanish Town, some survey respondents referenced that the small section of the Spanish Town neighborhood across the interstate had a larger number of Black residents. Additionally, like Greenwich Village, Spanish Town may not have been a safe haven for Black gay men and women. In Chandler's surveys, few survey respondents reported that Black gay men and women were visible in the neighborhood.

Chandler's surveys also provide insight into understanding Spanish Town as a gayborhood—a neighborhood with a strong visible presence of gay men and lesbian women that are often developed out of economically depressed or racially diverse areas of the city (Ghaziani 2015; Hunter 2015; Knopp 1997; Madden and Ruther 2015). In Greenwich Village, the ways that bohemians had forsaken social roles deemed appropriate for their class and gender often led to them being labeled sexually nonconforming, and gay people "used the openings created by bohemian culture to expand their public presence" (Chauncey 1994: 235). This bohemian neighborhood was the only legible gayborhood in the city of Baton Rouge in the 1980s. Several older interviewees told me that nicknames for the neighborhood in the 1980s, such as "Fairy Town" and "Fairy Ville", gestured toward the visibility of white gay men in the neighborhood, particularly with the use of "fairy" imagery (Chauncey 1994).

Many survey respondents reported on the presence of gay men in the neighborhood as more common in the 1980s than in previous decades. Gay men were connected in these accounts to the gentrification and development of historical conservation in the neighborhood, which is consistent with a history of gay men as historic preservationists (Fellows 2005). Neighborhood resident Gill described in his interview with Chandler that future changes in Spanish Town centered on a growing gay community:

I think the homosexual element is going to stay big. There's really no better place for them to go. This is established, it's quiet, they're accepted, and there are a lot of 'em. I don't think they create the kind of up-tightness in the old people that we did ten years ago…the gay people interact with the older people and help them cut their lawns and do a little landscaping for them. A lot of the landlords love 'em because when they move into a place it can be shambles, and then when they move out it's beautiful. (Chandler 1985: 85)

Gill's narrative of gay residents in the neighborhood used images of gay men, particularly white gay men, as beautifying neighborhoods through renovation and historical restoration. Their role in beautifying houses that are "shambles" is a key role that gay men play in urban gentrification and the creation of areas of historical preservation (Brink 2011; Ghaziani 2015; Hunter 2015; Knopp 1997; Lauria and Knopp 1985; Madden and Ruther 2015). Gill's tone—referring to the "homosexual element" and using mild othering language—also suggests that like racial integration of Spanish Town, the influx of gay men into the neighborhood did not erase histories of homophobic attitudes in the neighborhood.

A few of Chandler's surveys and interviews hint at the presence of lesbian women in the Spanish Town neighborhood as well. Chandler's detailed interviews included insights from women who identified as gay in the Spanish Town neighborhood. Shannon, a 30-year-old white divorced woman, wrote in "gay" in the survey as a response to a question about race, gender, and marital status. Shannon lamented that the neighborhood is "zoned in such a manner so that we cannot vote as a whole community. Thus our strength is diminished on certain issues that effect [sic] our community" (Chandler 1985: 91). This survey comment suggests that there was some solidarity within the neighborhood—possibly based on sexual orientation—but also an inability to turn that solidarity into political action.

Spanish Town used to be a big drug area. Then I think it turned into a big gay area, but I don't think that's so true anymore. I know there are a lot of gays here, but I wouldn't call this a gay garden by any means. There have been a lot of couples and straight people move in. I didn't move here just because I'm gay; I moved here because I love the neighborhood. Gay people are so transient…. Of the people who stay here awhile, maybe ten to twenty percent are gay; it's really hard to say. On this street, I would say about fifty percent of the people are gay. If there is a lesbian district in Spanish Town, it would probably be around this street. (Chandler 1985: 94)

Shannon lives in a section of Spanish Town that she described as "about fifty percent" gay or a "lesbian district" but not a "gay garden." Yet she also reported that this gay population is transient, possibly renters like many of the neighborhood residents. However, Shannon's interview provides insight to the presence of lesbian or queer women, a potential "lesbian district" on her street in the neighborhood. Lesbian and queer women territorialize space differently and rarely form distinct urban neighborhoods (Brown-Saracino 2019; Gieseking 2013, 2016; Moore 2015). For example, Japonica Brown-Saracino (2019) argues that queer women may be more likely to use diverse urban spaces, such as hair salons, coffee houses, and book stores, than gay bars. Lesbians and queer women may not have the economic power and flexibility to buy houses in gayborhoods (Moore 2015), and also are more likely to live in rural areas or small towns than gay men (Brown-Saracino 2019). So, the presence of a "lesbian district" in Spanish Town is noteworthy.

The culture of this neighborhood was a staging ground for the development of a wild Mardi Gras parade. The bohemian enthusiasm for eccentricity, artistry, and diversity coupled with the presence of young white gay men and lesbian women contributed to the grassroots development of a neighborhood parade that came out of this neighborhood solidarity.

6 Spanish Town Parades as Part of Gay Cultural History in Baton Rouge

I was walking through the Spanish Town Ball in 2015, a convention center packed with hundreds of krewe members in pink clothing dancing to live music, drinking, and displaying outrageous table decorations including huge light-up penises. I recognized one of my connections from the Krewe of Apollo, a tall white gay man named Chris dressed in a pink tutu and went over to say hello. Chris threw shade at my clothing selection—a sports coat with pink stripes and neon green pants—as being too formal and gestured to his own outfit as a better demonstration of what to wear. "This is like a block party, but inside and for everyone," he told me. He mentioned that his aunt is here, along with several cousins, because they ride in krewe floats during the parade. I complained briefly that this ball feels so much straighter than the Krewe of Apollo Ball, reflecting my own feelings of discomfort with the décor that seemed to resemble heterosexual bachelor and bachelorette partying with the predominance of penis imagery. Chris grabbed me by the arm to pull me closer in a moment of queer solidary. "Make no mistake," he said into my ear, "We started all of this." Chris asserted in this moment that although the Spanish Town Ball and Parade was now heavily influenced by heterosexual participants and culture, the parade had been started by members of the LGBTQ community. By bringing me into his declarative "we", Chris argued that not only gay men but also people like myself—someone he understood to be a lesbian or queer woman—were involved in creating these events. Although Chris has never lived in the Spanish Town neighborhood and was a child when the Spanish Town Parade started, he asserted vicarious citizenship over the neighborhood and parade. Chris's symbolic ties to the Spanish Town neighborhood through his gay identity contributed to his feelings of ownership and pride over the start of the major Mardi Gras event.

Throughout my interviews and fieldnotes, I often heard LGBTQ people in Baton Rouge describe the Spanish Town Parade as an event with queer origins that came out of an established gayborhood. There is not a clear documented history of the start of the Spanish Town Parade, and multiple competing narratives exist about how the first parade began. Two of these narratives position the origins of the parade within a history of racial integration and contestation within the neighborhood. One white heterosexual male interviewee and Spanish Town resident has loudly claimed that he and a friend started the parade in the early 1980s by paying a few young Black boys to parade around the neighborhood and pound on cardboard boxes for the two years before the official start of the Spanish Town parade. When the boys did not reappear after the second year, he got his flat-bed trailer and towed it around the neighborhood instead. Other interviewees described that the parade was planned by two "very creative" white men in the neighborhood, one of whom was an anthropologist. Second line parades are walking parades (e.g., without floats) that are part of the Black Carnival tradition (Barrios 2010; Stillman and Villmoare 2010). These two men purportedly watched videos of second line parades in New Orleans to get inspiration for the Spanish Town parade. They made up the name of SPLL in order to apply for a parade permit. One male interviewee stressed with a positive and respectful tone how "very creative" these men were in a manner that may have been signaling their sexual orientation. These two narratives—that the parade was started by two white men paying Black boys or by two white men culturally appropriating Black Carnival traditions—position white men in the neighborhood as starting the parade tradition by using Black artistry, labor, and cultural traditions.

The most common story from White and Black LGBTQ Baton Rouge residents was that the parade was part of a gay cultural tradition. The Spanish Town Parade came to my attention that second day I was doing research in Baton Rouge, when I attended a local Pride festival. I walked among the tables of organizations, chatting with people at each table about the Baton Rouge LGBTQ community and Mardi Gras. While speaking with a young Black lesbian woman who helps run a local group for young Black LGBTQ women, she asserted that she was most likely to attend the Spanish Town Parade or the "pink flamingo parade" to support their friends who ride floats in the parade because it was "our parade." In a phone interview with a white older lesbian who lived in Spanish Town and who I spotted at almost every Baton Rouge Mardi Gras event I attended, she exclaimed that "make no mistake, that parade was started by drag queens in a pickup truck." Many other interviewees and informants mentioned the presence of drag and drag queens in the parade as an important part of the gay cultural history of the event.

Other studies of the Spanish Town Parade reference the presence of drag queens at the early parades in the neighborhood. In an interview with a Spanish Town resident who recalled the 1981 parade, ''I looked out my apartment window [in Spanish Town] because I heard some music. A couple of drag queens and maybe two vehicles went by [on the street]. I remember thinking what the hell was that?" (Bowman et al. 2007: 299). Many interviewees and informants who went to the 1980s Spanish Town parades referenced the visibility of drag queens, including the walking krewe "The Sluts of '84," during those years. In a magazine interview, a longtime Spanish Town resident waxed nostalgic about the drag queens in the 1980s parades:

Then there were the drag queens; they would show up in, like, black leather and spiked heels, full beards. And we thought they were great, but they dropped out around '86 or something. The Advocate [the Los Angeles-based gay magazine, not the Baton Rouge newspaper] felt that the parade was getting way too heterosexual for them. (Hall 2016)

Some informants described these drag queens as not residents of the neighborhood, rather they lived "who knows where" and joined in the parade every year. The description of these queens—with black leather, spiked heels, and full beards—captures an erotic, amateur style of drag, as professional drag queens rarely sport full beards.

The visibility of drag queens in the 1980s was remarkable for several reasons. First, in the 1980s, drag queens had not yet become familiar to mainstream heterosexual audiences on shows such as RuPaul's Drag Race. Drag queens were probably only familiar to attendees of gay bars. Second, the visibility of drag queens in this Baton Rouge Mardi Gras parade parallels similar efforts in the 1980s in two other cities with Carnival: New Orleans and Rio de Janeiro. Only a few scholars have documented gay men's involvement in city-wide Mardi Gras events, and the only two cities with any information on them are New Orleans and Rio de Janeiro. In both of these cities in the 1970s and 1980s, gay men asserted their right to cross-dress and perform drag during Carnival events, often in defiance of municipal or statewide laws against cross-dressing (Carey 2006; Green 1999; Smith 2017). Drag played a symbolic role in the fight for public space and visibility for the gay community in these cities.

Third, drag queens became the symbol of gay visibility in the parade, regardless of whether or not the queens in question were residents of the neighborhood, rather than the mostly white gay neighborhood residents who were associated with gentrification and neighborhood beautification. Like my informant Chris from the Krewe of Apollo, these drag queens from outside the neighborhood may have been claiming a vicarious citizenship to the one visible gayborhood in Baton Rouge by showing up and being visible in the parade every year.

By marking LGBTQ community members as the originators of the parade, informants could also emphasize the cultural and social contributions of the LGBTQ community to Baton Rouge history. This unified community contribution may be part of establishing cultural citizenship and recognition (Lamont 2018; Rosaldo 1994; Stone 2016) or the right to be both different and respected. Drag definitely represents the ways that LGBTQ culture is different; gay respectability politics embraces neighborhood beautification and restoration more than drag, which is associated with gender non-conformity and queer radicalism.

Additionally, narratives of "we started this" may be emphasized by LGBTQ informants, because the queer origins of the Spanish Town parade are not as obvious anymore. In the magazine interview above, the Spanish Town resident decried the end of drag queen participation due to the parade getting "way too heterosexual." LGBTQ Baton Rouge residents attend the Spanish Town parade and also may claim vicarious citizenship over the origins of the parade. Many informants also described the parade as run by heterosexual men who don't live in the Spanish Town neighborhood, along with the parade being homophobic and transphobic at times.

7 Homophobia and Queer Culture in the Contemporary Parade

In 2014, the first year I went to the Spanish Town Parade the theme was "Flamingo Dynasty", a play on the Duck Dynasty reality show set in Northern Louisiana and the controversy over homophobia in the show. A few weeks before the parade, I met the organizing committee members while helping them paint large wooden cut-outs of flamingoes bright pink for the annual "flocking" event of attaching the cut-outs of the flamingos to posts in a Baton Rouge lake. Baton Rouge Carnival had a tradition of people swimming out to steal the cut-outs and display the flamingos in their houses or yards. I was surprised at the time that all the Spanish Town organizers there were white men who were presumably heterosexual in demeanor and self-presentation. They answered my questions about the parade as a fundraiser and how to best approach conducting research at the parade. Chuck, a white man in his sixties who managed the fundraising for the group, flirted with me carelessly, even though I had been straight forward that I was a queer person studying LGBTQ involvement in the parade. He slipped me a t-shirt from last year's parade that his krewe had made, remarking that he usually made girls show him their boobs for a t-shirt but winked as he told me that he would let it pass this time. Chuck outlined the spirit and intention of the parade: to raise money for charity, to have a good time, and to have adult-oriented fun. "Children already have Disneyland," he remarked. "Not everything has to be for children." Although children attend the parade, the adult-oriented ethos of the event evoked queer political resistance to children, family, and respectability (Edelman 2004). He confided in me that there was a section of the parade route without alcohol but also an area in the heart of the Spanish Town neighborhood where "boobs for beads" ritual disrobement was permitted. There's a little bit of something for everyone at Spanish Town, and there is also something to insult everyone. The Spanish Town Parade is diverse politically and sexually, an ethos that was reflected in many interviews and conversations I had throughout my fieldwork in Spanish Town.

Yet my interactions with heterosexual organizers of the parade reflect a combination of heteronormativity and participation in queer culture. Jones, a white man in his forties with a bushy beard, regaled me with stories about his costuming and cross-dressing for the event. Traditionally, attendees and parading krewes wear hot pink accessories and clothing, along with flamingo-related gear. Jones commented that he had laid out all his pink clothing and realized he had more pink clothes than "a 10-year-old girl." He told stories about what he described as "bad cross-dressing by straight men" at the parade and ball. The drag he described reminded me of cross-dressing that is done in fraternity hazing rituals and fundraisers. In my notes on the aesthetic of parade goers, I underlined in bold how often I saw "white middle-aged women in ponytails with pink tutus", "bad white frat-boy drag", and "white older men in pink shirts that said 'This is Your Girlfriend's Shirt.'" In her work on Pride parades, Katherine Bruce writes about heterosexual attendees of these parades; that the parades allow even heterosexual attendees an opportunity to flaunt heteronormativity and that "they too challenge this code in the world while at the same time enjoying a rare break from its restrictions" (Bruce 2016: 186). My first impression is that the Spanish Town Parade is an opportunity for everyone to wear pink and be a little wild, embracing the bohemian spirit of the earlier days of the Spanish Town parade.

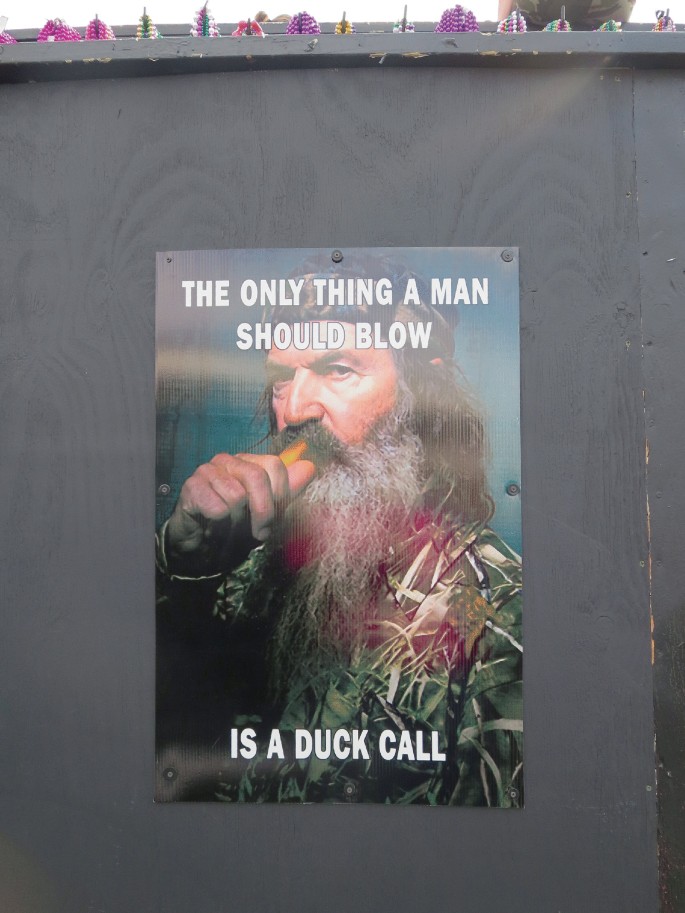

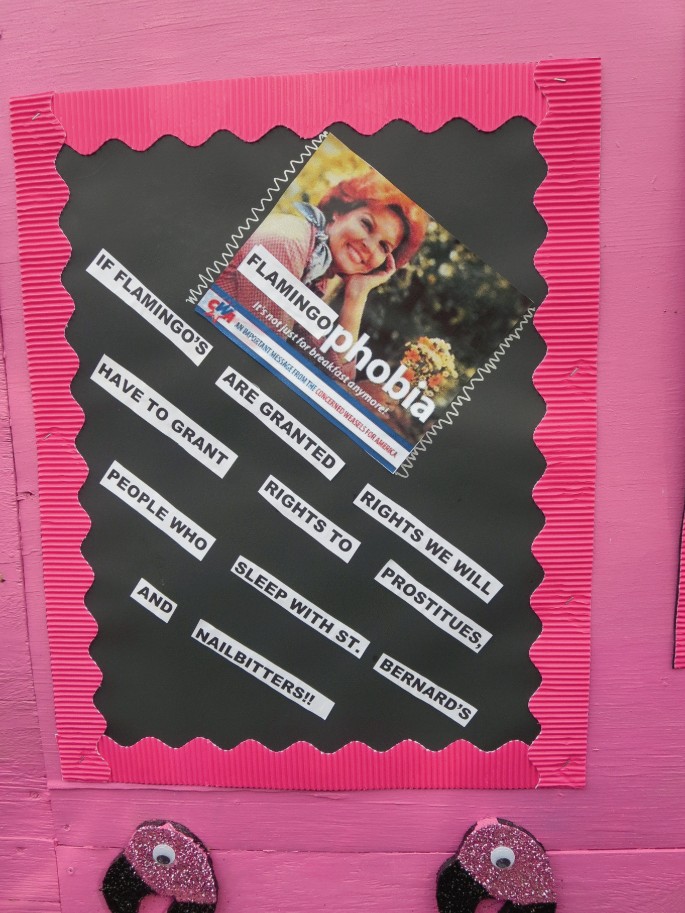

Touring the Spanish Town floats before the parade, I noticed that the floats included political and social commentary and often scathing satire that was both supportive and critical of Duck Dynasty. There was just as much homophobic commentary as there was LGBTQ-supportive commentary. Many floats supported the homophobic attitudes expressed on Duck Dynasty. These floats were dressed up for duck hunting, covered in camouflage, netting, and palm fronds, and exclaimed statements like "It's just my opinion!", in support of Duck Dynasty patriarch Phil Robertson's anti-gay sentiments that led to the discontinuation of the show. Other floats were more blatantly homophobic, showing the patriarch with a duck call in his mouth stating "The Only Thing a Man Should Blow is a Duck Call" (Fig. 6.2). Many more floats mocked the homophobic attitude of Robertson. Over a dozen floats positioned Robertson as a gay man, a drag queen, or having sex with a male flamingo (Fig. 6.3). One float titled itself Flamingo(phobic) Dynasty and satirized well-known homophobic politicians' statements by replacing their references to gay men to be ones about flamingos (Fig. 6.4). I remembered interviewing two LGBTQ members of Baton Rouge community—an older white lesbian and a young white transgender man—who abhorred the parade, suggesting it offered up LGBTQ culture as something to be mocked and allowed straight people to consume gay culture.

(Source Image by author)

Spanish Town float about Duck Dynasty patriarch

(Source Image by author)

Spanish Town float

(Source Image by author)

Spanish Town Flamingophobic Dynasty float

Walking through the parade floats, I was immediately aware of the limitations of the Spanish Town Parade diversity; almost all the floats were occupied by all-white krewes. Less than five krewes had Black participants on their floats and these floats had exclusively Black participants. This kind of racial segregation in Carnival krewes is startlingly common (Gill 1997), but I was surprised to see how dramatic krewe segregation was at an event so frequently described as bohemian and diverse.

Several informants described both the parade and the Spanish Town Ball to me as "everyone having their own party next to each other." The Spanish Town Parade has grown and changed significantly since its start as a small gayborhood parade. The parade has become a large community event. From my vantage point on the lofty judges' platform during one parade, I took a shot of the crowd, a sea of tens of thousands of people wearing pink crammed in the narrow streets of the Spanish Town neighborhood (Fig. 6.5). Walking through the streets of the parade while it took place, I wandered through blocks of families having a barbeque out on the street with their kids, corners that were mostly Black parents with young children, a block of mostly white teenagers making out, and a quiet block that included a large group of white queer senior women. One area in the heart of the Spanish Town neighborhood was blatantly queer, with drag queens, butch lesbians, and other queer partiers celebrating together. I wandered in and out of house parties being thrown by neighborhood residents. I could not decide whether this collective partying furthered or lessened the queer visibility of the parade.

(Source Image by author)

Street view of Spanish Town parade crowd

The queer politics of the parade at times seems celebratory and at other times seems a project consumed by heterosexual participants. Elements of the queer origins of the parade are evident in the current event, particularly its anti-family sentiment, cross-dressing, flexibility, and diversity. The continuing ethos of "bad taste" at the event reflects its bohemian origins. Other scholars have suggested that longtime parade organizers and participants "argue that the high exposure [of the parade] has sapped the parade of its queer politics" (Bowman et al. 2007: 300). Throughout my fieldnotes I did note the consumption of queer culture and fashion by parade attendees, particularly the attention given to white gay men who were dressed in drag or outrageous costumes. Drag queens who I interviewed remarked that they often got frustrated by being constantly stopped by presumed straight attendees to take group pictures with them.

The Spanish Town Parade began in a quiet bohemian neighborhood that was the only visible gayborhood in the city of Baton Rouge. The small, spontaneous parade of "drag queens in pickup trucks" started in the 1980s and transformed into the largest parade during Baton Rouge Mardi Gras. The growth and diversity of the Spanish Town Parade may be linked to the same trends as the decline of gayborhoods, the emergence of post-gay culture in which sexual identity is less consequential (Ghaziani 2015). Instead, I approach the heterosexualization of the Spanish Town Parades as part of a broader trend of the consumption and appropriation of gay culture, fitting into studies of bars and other LGBTQ spaces that are transformed by the increased involvement of heterosexual participants (Orne 2017). In the case of the Spanish Town Parade, the increased participation by heterosexuals did not diminish the vicarious citizenship that LGBTQ residents of Baton Rouge expressed over the origins of the parade. The contemporary parade also still shows signs of its queer origins and is widely attended by LGBTQ people. However, the Spanish Town neighborhood and parade have both dramatically changed since the 1980s. Gay Spanish Town residents complained to me about how unaffordable the neighborhood had become as it became trendy and less connected to its bohemian past. Similarly, the contemporary Spanish Town Parade includes a complicated mix of homophobic sentiments, heterosexual celebration of temporary gender non-conformity, and heterosexual control over the parade organizing.

References

-

Barrios RE (2010) You found us doing this, this is our way: criminalizing second lines, Super Sunday, and habitus in post-Katrina New Orleans. Identities 17(6):586–612

-

Bowman RL, Kitchens M, Shkreli L (2007) FEMAture evacuation: a parade. Text Perform Q 27(4):277–301

-

Braunstein R, Fulton BR, Wood RL (2014) The role of bridging cultural practices in racially and socioeconomically diverse civic organizations. Am Sociol Rev 79(4):705–725

-

Brink CJT (2011) Gayborhoods: intersections of land use regulation, sexual minorities, and the creative class. Ga St UL Rev 28:789

-

Browne K (2007) A party with politics? (Re)making LGBTQ pride spaces in Dublin and Brighton. Soc Cult Geogr 8(1):63–87

-

Brown-Saracino J (2019) Aligning our maps: a call to reconcile distinct visions of literatures on sexualities, space, and place. City Commun 18(1):37–43

-

Bruce KM (2016) Pride parades: how a parade changed the world. New York University Press, New York

-

Carey A (2006) New Orleans Mardi Gras Krewes. GLBTQ Encycl Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Queer Cult, pp 1–4

-

Chandler TW (1985) Spanish Town: neighborhood as place. PhD Thesis, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge

-

Chauncey G (1994) Gay New York: gender, urban culture, and the makings of the gay male world, 1890–1940. Basic Books, New York

-

Costello BJ (2017) Carnival in Louisiana: celebrating Mardi Gras from the French quarter to the Red River. Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge

-

Crary J (2001) Suspensions of perception: attention, spectacle, and modern culture. MIT Press, London

-

Debord G (2012) Society of the spectacle. Bread and Circuses Publishing, London

-

Delanty G, Giorgi L, Sassatelli M (2011) Festivals and the cultural public sphere. Taylor & Francis, London

-

Donlon J (n.d.) It's a very pink day in my neighborhood. Folklie in Louisiana. Retrieved December 31, 2019 http://www.louisianafolklife.org/LT/Articles_Essays/its_very_pk_dy.html. Accessed 31 Dec 2019

-

Edelman L (2004) No future: queer theory and the death drive. Duke University Press, Durham

-

Fellows W (2005) A passion to preserve: gay men as keepers of culture. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison

-

Gamson J (1998) Freaks talk back: tabloid talk shows and sexual nonconformity. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

-

Ghaziani A (2015) There goes the Gayborhood? vol 63. Princeton University Press, Princeton

-

Gieseking JJ (2013) Queering the meaning of 'neighbourhood': reinterpreting the lesbian-queer experience of Park Slope, Brooklyn, 1983–2008. In: Taylor Y, Addison M (ed) Queer presences and absences, genders and sexualities in the social sciences. Palgrave Macmillan UK, London, pp 178–200

-

Gieseking JJ (2016) Crossing over into neighbourhoods of the body: urban territories, borders and Lesbian-Queer bodies in New York City. Area 48(3):262–270

-

Gill J (1997) Lords of Misrule: Mardi Gras and the politics of race in New Orleans. University Press of Mississippi, Jackson

-

Green JN (1999) Beyond carnival: male homosexuality in twentieth-century Brazil. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

-

Greene T (2014) Gay neighborhoods and the rights of the vicarious citizen. City Commun 13(2):99–118

-

Hall C (2016) In the pink: the origins of the Spanish Town Mardi Gras parade. Country Road Magazine. https://countryroadsmagazine.com/art-and-culture/people-places/history-of-spanish-town-parade/. Accessed 10 Jan 2020

-

Heap C (2008) Slumming: sexual and racial encounters in American nightlife, 1885–1940. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

-

Hunter M (2015) All the gayborhoods are White. Metropolitics

-

Isch M (2016) Capitol Park and Spanish Town. Arcadia Publishing, Mount Pleasant

-

Kinser S (1990) Carnival, American style: Mardi Gras at New Orleans and Mobile. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

-

Knopp L (1997) Gentrification and gay neighborhood formation in New Orleans. In: Homo economics: capitalism, community, and lesbian and gay life. Routledge, New York, pp 45–59

-

Lamont M (2018) Addressing recognition gaps: destigmatization and the reduction of inequality. Am Sociol Rev 83(3):419–444

-

Lauria M, Knopp L (1985) Toward an analysis of the role of gay communities in the urban renaissance. Urban Geogr 6(2):152–169

-

Madden JF, Ruther M (2015) Gayborhoods: economic development and the concentration of same-sex couples in neighborhoods within Large American Cities. In: Regional science matters. Springer, Berlin, pp 399–420

-

Moore MR (2015) LGBT populations in studies of urban neighborhoods: making the invisible visible. City Commun 14(3):245–248

-

Orne J (2017) Boystown: sex and community in Chicago. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

-

Rosaldo R (1994) Cultural citizenship and educational democracy. Cult Anthropol 9(3):402–411

-

Rupp LJ, Taylor V (2015) Drag queens at the 801 Cabaret. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

-

Rushbrook D (2002) Cities, queer space, and the cosmopolitan tourist. GLQ J Lesbian Gay Stud 8(1):183–206

-

Sinclair D (1998) Equal in all places: the civil rights struggle in Baton Rouge, 1953-1963. La Hist: The J La Hist Assoc 39(3):347–366

-

Smith HP (2017) Unveiling the muse: the lost history of gay carnival in New Orleans. University Press of Mississippi, Jackson

-

Stillman PG, Villmoare AH (2010) Democracy despite government: African American parading and democratic theory. New Polit Sci 32(4):485–499

-

Stone AL (2016) Crowning King Anchovy: Cold War gay visibility in San Antonio's urban festival. J Hist Sex 25(2):297–322

-

Stone AL (Forthcoming) In my dad's gun room there's an 8x10 picture of me in drag: drag and respectability in the deep south. In: Berkowitz D, Windsor E, Han C-S (eds) Male femininities. NYU Press

-

Wetherell M, Stephanie T, Simeon JY, Open University (2001) Discourse theory and practice: a reader. Sage, London

-

Yee A (2015) The most racially segregated cities in the South. Facing South, May 8

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Reprints and Permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Stone, A.L. (2021). Wearing Pink in Fairy Town: The Heterosexualization of the Spanish Town Neighborhood and Carnival Parade in Baton Rouge. In: Bitterman, A., Hess, D.B. (eds) The Life and Afterlife of Gay Neighborhoods. The Urban Book Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66073-4_6

Download citation

- .RIS

- .ENW

- .BIB

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-66073-4_6

-

Published:

-

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

-

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-66072-7

-

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-66073-4

-

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental Science Earth and Environmental Science (R0)

meyersbrestiong1961.blogspot.com

Source: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-66073-4_6

0 Response to "Drunk Democrat in Texas Wearing Dress in Gay Band"

Post a Comment